Bourbon

America’s distinctive spirit

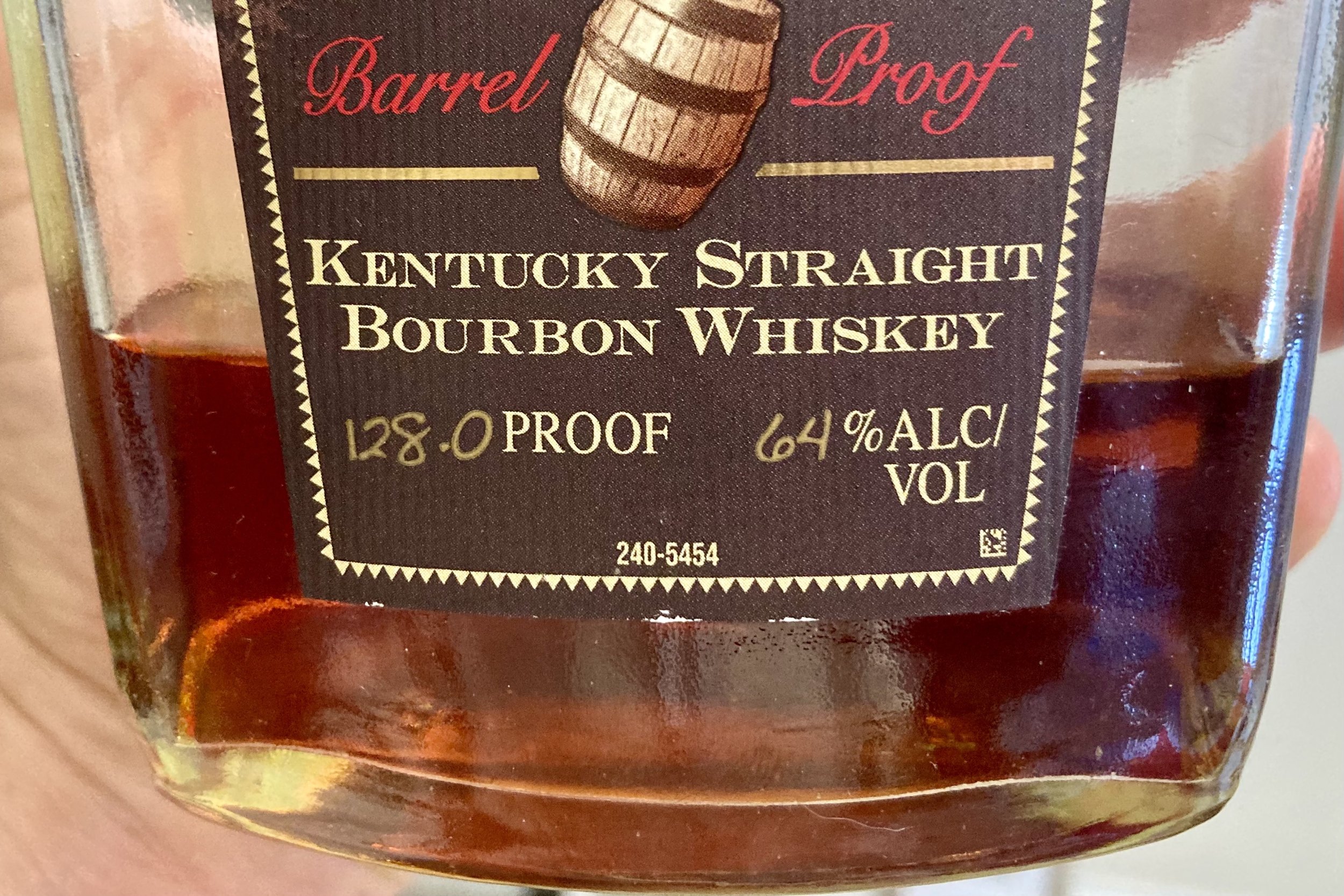

The law states that bourbon must be made in the US from a majority corn mash bill (51+%), distilled to no more than 80% ABV and stored in new charred oak barrels at no more than 62.5% ABV with no additives. Contrary to popular belief, bourbon does not have to be made in Kentucky! The regulations began as a way to ensure a standard quality of bourbon and continued to evolve over time. Many stories relate to the origins of bourbon, a lot of them stir up controversy. Most of them are probably folktales, emerging only because the truth is not actually known. So mysterious!

When settlers first arrived in America, distilling spirits from a mostly corn mash was not common practice. In fact, whiskey wasn’t popular until after the Revolutionary War when Britain surged molasses taxes, making rum too expensive to produce. Yes, that’s right, settlers were mostly rum drinkers. I’ll save that story another time -- this article is about bourbon.

Farmers were the first to make whiskey, distilling spirits from their excess grain to keep it from going to waste. It was not only necessary to add some distilled spirit to water to make it potable, but the spirit was their form of currency for goods and labor. And rye was the primary grain used to make whiskey because that’s what was readily available in the North East.

As settlers moved west of the Appalachians to Kentucky for “corn patch and cabin rights,” rye was harder to come by, so they grew the native crop, maize/corn. These farmers had vast amounts of land that could grow a lot of corn, meaning they could also distill a lot of whiskey. That whiskey needed to be stored and later transported, which required barrels. Legend has it that farmers would reuse barrels that previously stored things like fish, meat or pickles. Sounds gross, right? To get rid of those flavors, the distiller charred the barrels before tossing in the whiskey. I find it hard to believe that any amount of charring could eliminate the fishiness that seeped into the wood, but it’s one theory explaining how charred barrels came to be in the bourbon industry. And who knows, maybe those fishy notes complemented the whiskey.

Another version of the story claims Elijah Craig was the first to store his whiskey in charred barrels. Craig was a baptist preacher, talented distiller and the “father of bourbon.” As the story goes, a fire started in his barn housing a bunch of whiskey barrels. Though, the fire charred the barrels, Elijah couldn’t put them to waste. So, he aged whiskey in the charred barrels, only to notice the whiskey developed into a deliciously rich, sweet spirit with some time. Thanks to this happy accident, he charred all of his whiskey barrels from that point on. Not everyone believes Elijah Craig to be the “father of bourbon” (I, for one, think there was actually a mother of bourbon), but he was definitely one of the first bourbon distillers.

Others believe the Tarascon Brothers brought the charred barrel to the bourbon industry. They moved to Louisville from Cognac, France, and knew charred barrels were essential in developing the rich, sweet flavors of cognac. They also understood that a spirit similar to cognac appealed to the French settlers in New Orleans. So it’s said that the brothers shipped their whiskey in charred barrels down the Ohio River to New Orleans, which would take about 3 months. That was enough time, especially in the heat, for the whiskey to develop into a wonderful spirit. And they were right, the settlers loved their whiskey. Eventually the demand for it grew, and people started requesting “the whiskey that they sell on Bourbon Street,” which eventually turned into “that bourbon whiskey.”

That’s just one theory for how bourbon got its name. Others say it was named after Bourbon County, KY, or it was a marketing ploy to symbolize high-quality whiskey to the New Orleanians (referencing the royal House of Bourbon). No one actually knows where the name bourbon came from or who was the first person to age bourbon in charred barrels. We should just be thankful that someone figured it out.

If the bourbon you’re sipping on while reading this is a “straight bourbon,” it was aged for at least two years in new, charred oak barrels or four years if there’s no age statement on the label. If it says “Kentucky,” you know it was made in Kentucky. If your bourbon was “bottled-in-bond,” (BIB) now that’s something special.

The Bottled-in-Bond Act states whiskey must be distilled by one distiller at one distillery during one distillation season. It also must be aged in a federally bonded warehouse for a minimum of four years and bottled at 100 proof (50% ABV). This act was created as a way to ensure pure, high-quality whiskey. You see, once whiskey became popular in the US, there were people who aimed to make a quick buck by exploiting bourbon. These guys would mix in anything and everything to make their unaged whiskey more palatable, so that they could sell it without taking the time to age it. Even worse, they were using neutral grain spirit and calling it whiskey. Ingredients blended in were not only gross, like charred animal bones and tobacco juice, but quite toxic, like ammonia and turpentine. Some say that’s just folklore, but whiskey was not regulated in the 1800s, so “distillers” could do whatever they wanted. Anyways, these con artists were called rectifiers, and the way they tainted the name bourbon motivated distillers to fight back. (Pro-tip: I’ll usually lean towards picking up BIB American whiskeys because I haven’t found one that I didn't like.)

Edmund H. Taylor, a politician and distillery owner, was instrumental in passing the 1897 Bottled-in-Bond Act. With these laws in place, consumers could rest assured their whiskey was high-quality. The Pure Food and Drug Act of 1907 and the Taft Decision of 1909 transcended these regulations by defining “straight whiskey” versus “blended whiskey” and controlling what could go on the label. These laws further ensured a high standard for whiskey.

In 1935 the Federal Alcohol Administration Act mandated that bourbon had to be aged in new charred oak barrels. Emphasis on new. Some people say this was done to preserve tradition and/or quality of the bourbon. But the act was a part of the New Deal following the Great Depression, and it’s said this regulation was heavily lobbied by the coopers union and lumber industry. Some go so far as to credit Wilbur Mills, a future representative of Arkansas with putting this law in motion. This claim would hold more credit if Mills was a representative at the time because Arkansas has a large timber industry. Regardless of the true motive, ensuring a high demand for barrels seems like a good way to create and sustain jobs in these industries. And we should all be thankful because bourbon would not be what it is today if it were aged in used barrels.

In fact, all the regulations surrounding bourbon make it the delightful, very popular whiskey that we know. The flavors that come from fermented corn are subtle and lend to the rich flavors extracted from the barrel. Charring the barrel increases the sweet, caramel and vanilla notes and using new barrels ensures plenty of those flavors are extracted by the bourbon.