Japanese Whisky

The desirable and unbridled whisky category.

In recent years, Japanese whisky has picked up a lot of hype with consumers. So much so that the prices of some bottles have increased by five times their original market price (like Hibiki 17 year, which went from around $150 to $800 almost overnight). But why? What’s the big deal? What makes Japanese whisky so special?

It is so difficult to define Japanese whisky. Why? Unlike most other whiskey producing countries, there are currently no regulations for Japanese whisky. This means it doesn’t have to be produced in Japan nor does it have to be derived from 100% fermented grains. In fact, it only has to contain 10% grains in the mash to be called “whisky” in Japan. Crazy, right?

In their defense, Japanese whisky is practically brand new compared to other countries. Irish monks were distilling whiskey in the 12th century, the Scots began shortly after that and American whiskey has been around since the 17th century. Whisky didn’t make it to Japan until the mid-19th century when US Commodore Matthew Perry arrived to convince the Japanese to open up foreign trade. He brought the emperor 110 gallons of American whiskey to help make his case. And production of whisky didn’t start in Japan until the 1920s. Meaning, Japanese whisky hasn’t even been around for 100 years!

Now, it’s a little easier to understand how unregulated Japanese whisky is when you consider it took the US almost 300 to start developing our whiskey regulations. Not to mention, the demand for Japanese whisky didn’t spike until 2013 when Yamazaki 22 year old Sherry Cask was awarded “World Whisky of the Year” by Jim Murray. Hence the recent surge in popularity and prices.

Not to fret, Japanese whisky regulations are already on the horizon. You can read the detailed plans in an interview with Japan’s whisky expert, Mamoru Tsuchiya, here. But generally speaking, Japanese whisky will have to be made from grain only mash, fermented and distilled in Japan, and aged in Japan for no less than 2 years in wood containers. Sounds about right. And distilleries in Japan have already been moving more towards abiding by these potential future regulations.

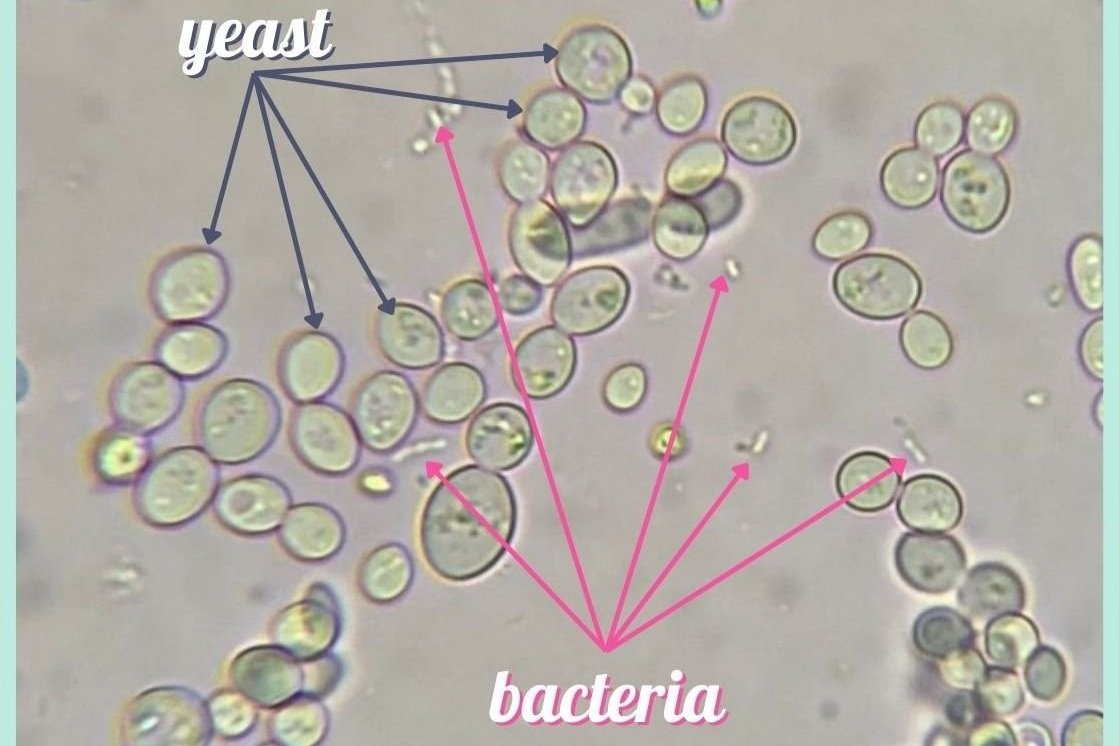

Now that I got that out of the way, let’s talk about what differentiates Japanese whisky from the rest of the big players, like Scotch for instance. One major differentiator is that whisky distilleries in Japan do not exchange whisky with one another. This is important to point out because the Japanese whisky style is similar to and inspired by blended Scotch whisky. For reference, popular blended scotch brands like Johnnie Walker, Ballantines and Dewars use 40-50 different scotches from various distilleries in their recipes. To mimic this, Japanese distilleries are producing many different styles of whisky so that they can create their various blends internally. Yamazaki Distillery (owned by Suntory), for example, can create upwards of 70 different malt whisky because they have 2 different types of fermentations, 8 different stills and 5 different casks. All of these combinations means they can create whatever whisky expression they’d like without depending on other distilleries’ production. Because of this, it’s rather challenging to define the characteristics of any Japanese distillery. They’re all making a huge variety.

One of the reasons why Japanese whisky is so desirable is because their style is essentially (not always technically) that of a blended whisky. The flavor profiles tend to be more versatile and appealing to a wider range of palates because they’re typically more delicate or “drinkable.” Because Japanese distillers are able to blend a variety of styles of whisky, the flavor profiles aren’t overpowering. Even the peated Japanese whiskies have delicate wisps of smoke as compared to Islay single malt scotches.

Another Japanese whisky differentiator is the use of the elusive mizunara cask. Mizunara oak (quercus crispula), aka Japanese or Mongolian oak, has spiked the interest of many distillers both inside and outside of Japan. The Japanese distilleries started using mizunara as a last resort during World War II when they were unable to import any of the casks typically used in Japan, like ex-bourbon barrels. When whiskey is aged properly in mizunara, it can develop notes of coconut, sandalwood and incense. Sounds nice, right? But not every distillery uses the cask properly. As it turns out, it’s very challenging to work with for a couple of reasons. Number one, the wood is very porous, making leaking a huge issue when it comes time to store the spirit. Nevertheless, many distilleries take their chances and hope that the reward of using this rare cask outweighs the leaky risk. The other issue with mizunara oak is that the trees don’t grow straight, meaning a tree needs to be over 200 years old before it’s the proper size to be harvested to make a barrel, which can also make it a pricey barrel.

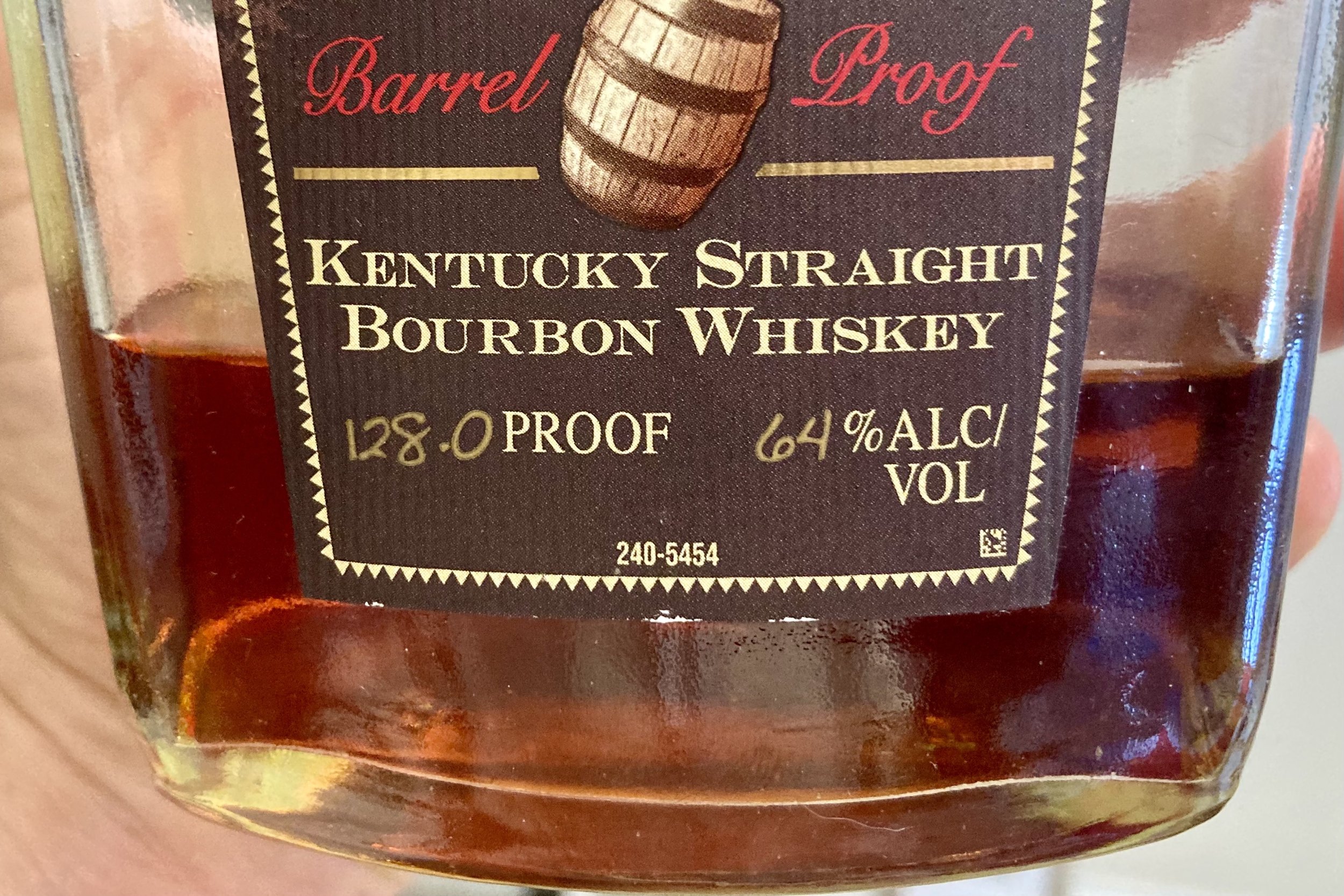

Suntory is a big proponent for mizunara casks and whisky aged in these casks is blended into most of their products. I hear the Yamazaki Mizunara series embraces the flavors of mizunara exceptionally well, but I cannot speak from experience (it’s pricepoint is just a little too high). Like I said above, not every distillery that uses mizunara oak uses it properly. Whiskey needs adequate time in casks to develop desirable flavors. Have you ever had a whiskey where it tasted like you were gnawing on a piece of wood? This is common in many young American whiskeys probably because that whiskey didn’t sit in the barrel long enough. When a whisky is too young, it strips out some of the tannins of the oak without having enough time to to interact with the wood, oxidize and evaporate, which creates the beautiful flavors of baking spices, caramel, maple, cocoa and honey. The same effect will happen with any cask, especially mizunara casks where 15-20 years is the happy-minimum to develop those delightful coconut and sandalwood notes. Keep in mind, this also depends on factors like climate. Regardless, many distilleries using mizunara are not giving the whiskey the proper time it needs in the cask. Most are finishing or aging for only a few years in mizunara just to put the premium “mizunara” callout on the label. (With that being said, if anyone gets to try Angels Envy Mizunara Oak released on September 1st, please let me know how it is...)

Despite my current hesitation to buy bottles of Japanese whisky, I’m very excited to see what whiskies are produced in the future. Distilleries in Japan seem to be more open to experiment and innovate unlike most other established distilleries that are held back by regulations and tradition.

If you’re curious why I use both “whiskey” and “whisky” spellings in this article, I describe the difference here.